Building on a long tradition of addressing issues that matter most to the community, and a commitment to engaging in ongoing learning alongside our stakeholders, The Denver Foundation is hosting in-depth discussions of the challenges, opportunities, and community-led solutions informed by focus areas identified in our new Strategic Framework: economic opportunity, education, environment and climate, housing, and transportation.

Our October Leading & Learning event was focused on Housing in Metro Denver and rural parts of Colorado. The Denver Foundation is focused on supporting work addressing affordable housing, housing stability, and aiding those experiencing homelessness with a specific focus on Racial Equity.

Special guests, Andrea Chiriboga-Flor and Jennie Rodgers (bios below) offered their insights on how the pandemic has influenced housing instability, historical housing policies that prevented homeownership, and policy efforts to shield communities from housing insecurity.

Andrea Chiriboga-Flor (she, her, ella) is the State Director for 9to5 Colorado, a grassroots member-based organization dedicated to fighting for womxn’s rights in and outside of the workplace. Her work with 9to5 began as a transit organizer and evolved into building the foundation for 9to5’s housing justice movement work. After college, she worked at a Spanish-language immersion childcare center in Boston and organized workers to push for benefits and overtime. In 2016, she co-founded Colorado Homes For All, which is based on the national housing justice movement led by Right to the City Alliance.

Jennie Rodgers leads Enterprise Community Partners’ work with local partners to increase and deploy resources for affordable housing, advocate for local and state affordable housing policy, and provide technical assistance and training to local partners. Ms. Rodgers has 25+ years of experience in the arena of affordable housing policy, finance, and development. She has worked in the nonprofit, private, and government sectors on urban and rural housing initiatives. Before joining Enterprise, Ms. Rodgers led the Community Strategies Institute, an affordable housing, and community development consulting firm based in Denver, Colorado.

View Past Events in this Series

Key Takeaways

Q: I’m going to start with a broad question, could you frame up for us what do you think are the biggest issues that we’re seeing in housing today in the Denver metro area?

Jennie Rodgers (JR): Sure. I think especially with the pandemic, housing instability is our biggest issue and as Dace has said, it’s driven by many factors. One, we don’t have enough units, just plainly, to house everybody who needs an affordable home in Colorado and that instability is really leading to a potential increase in homelessness or increase in homelessness, people having to move. And even pre-pandemic, we had huge numbers of people who are housing insecure, which means that they’re paying 30 or 50% of their income or more for housing. And that housing instability, due to the pandemic and due to our lack of units has also led to displacement in areas of change because of gentrification and household instability. So I would say that those are our biggest issues.

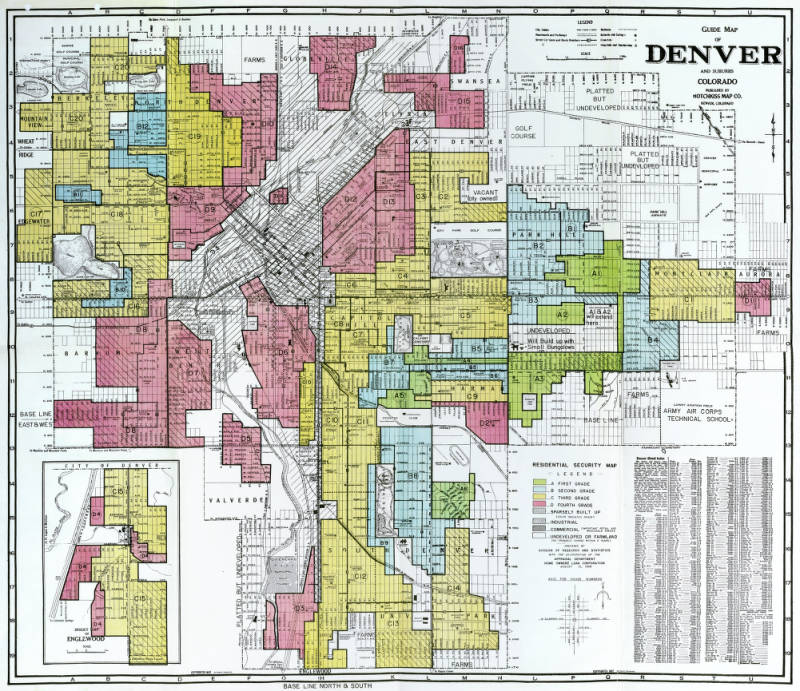

Andrea Chiriboga-Flor (ACF): There’s a lot. The fact that housing is so incredibly commodified in Colorado and in our country makes it so there’s no narrative around housing being a human right, even though we acknowledge it’s a basic necessity. I think there needs to be a huge shift in the way we think about housing, and who deserves housing. Our institutionalized racism, there’s a legacy of redlining that is still impacting where folks are today, and current practices excluding certain groups from housing because of where they come from. For example, we’ve had folks who are asked for their papers when they’re applying to housing, or in some cases where they’re already living, facing discrimination because of their race.

Q: Jennie, I wonder if you could build a little on what Drea was talking about in terms of historical context, how we got here. What’s the arc of how and why housing affordability became such an issue in our community?

JR: Yes. There are many issues that have led us here. Certainly the first is institutional racism, including redlining, we were really lucky to have you [The Denver Foundation] sponsor an exhibit we brought to Colorado in 2019 called Undesign the Red Line. And I have to say, I’ve been in this industry for 30 years and only recently really learned of the history of racist practices in the housing industry led by the federal, state, and local governments. It was horrifying to realize that I didn’t understand the full depth.

If we back all the way up into the 1930s, it’s interesting, the federal government had actually started to build housing, after the Great Depression to put people in decent homes. Only, they chose to do it in a racist way where they had White homes and non-white homes and they actually split communities. The White homes were nicer than the non-white homes and the homes were located in different areas. And this was our first step into public housing. Those practices rolled forward into lending criteria that the Federal Housing Authority mortgage underwriting criteria were based on, which is why we call it redlining. Maps were created to show areas of red, yellow, green, and blue. The areas that were red and yellow were occupied by African American households, Latinx households, Jewish people, Irish, and Italians. It was a blatantly racist way of putting people into certain areas and making sure that folks couldn’t borrow to buy a home in areas marked red or yellow.

In Denver, we call it the inverted L where those redlining maps have led to communities where homes have not been able to be kept up as and some people still can’t access the capital necessary to do so. We don’t have as much public infrastructure in those areas. There’s disinvestment. And now, as we see in Denver especially, there’s a lot of gentrification of those areas. Think of Five Points or Highland, it is absolutely not a coincidence that those areas that are close to downtown and might not have been as popular for people to live in at some point and became strong, resilient communities for people of color, those people are now getting pushed out because of the areas rising popularity and increasing cost. I think we have to acknowledge that history as we think about solutions and we think about rectifying the system and

JR: Drea brings up a really good point that in America, housing is a commodity. Unless you’re working with the aid of a nonprofit organization or have community ownership, like cases 9to5 works on, people are at risk of losing housing because of our systems, putting landlords at risk too. Enterprise has been doing some research and BIPOC landlords who own smaller properties are having a harder time in the pandemic maintaining their units if they can’t access rental assistance. Putting renters in those households at risk as well. Some of the other threats are obviously we have higher unemployment rates for people who work in the service industry who may tend to have the very lowest incomes and/or be BIPOC themselves and there’s this cascade of issues that leads to higher housing costs, higher displacement, lower condition of units, and really disparity in the housing system.

Q: Redlining is a very clear example of racial inequity in housing. Drea, what would you add? What are some things that you’re seeing that are examples of racial inequities that are contributing to this landscape?

ACF: Our history in general in this land is tied to colonization practices, taking land from indigenous people, bringing Black folks forced from Africa to be slaves here. All of those pieces still add up to where we are today and there are lasting legacies in why we think about property in certain ways. Laws tied to voting rights are tied to property rights which are tied to gender and race. Part of what we need to do to fundamentally change our housing system and the way we think about housing and property and who is deserving of it is to recognize and decolonize wealth and property and the way we invest and opt for investing in collective liberation.

Something else that I mentioned before is community stewardship of land. We use the term stewardship now, more than ownership because we do believe that this is the collective responsibility and that kind of culture mentality is really what keeps communities safe and secure, and stable. It’s becoming more prevalent through resident-owned communities or community land trusts but hasn’t stretched beyond those communities because of our culture of individualism and property rights. And so those are a little bit more abstract ideas of why we are where we are today, but if we don’t recognize all those different pillars and what needs to be done, then we’re really going to continue to perpetuate these systems that leave folks homeless.

Q: Drea, I’d like to talk about what grassroots communities are doing to create change in the system. Could you share with us some of the campaigns and work that you’ve been doing in the organizing space where communities are really using their voices?

ACF: Yeah. So in 2016, 9to5 and some other groups came together to create a coalition for the first time, in a while, a grassroots housing coalition. It was really made up of only grassroots organizations, space building organizations to focus on system change work. Overwhelmingly, the people in our coalition said, “rent control is needed here.” They know it exists in other places. I think there’s a lot of misrepresentations about what that actually means in practice because it can mean a lot of different things. Most of the time it means a cap on rent increases. But it can also mean rolling back rent. It’s a concept that’s very stigmatized here but it is something that energizes our base. That’s what people are excited to do is to overturn the ban on rent control so counties and municipalities can really take control and address the housing crisis as they see fit. That’s an ongoing legislative campaign. Yet it might not be coming back this legislative session, unfortunately, but not due to 9to5 or our coalition, but because of political dynamics.

The other big piece of work is through manufactured housing or mobile home parks. We started working on this issue in 2014 when residents of two mobile home parks were set to be displaced in southwest Denver. These parks housed about 90 families. A lot of folks were undocumented or mixed-status families and for folks not familiar with mobile homes, they’re not actually mobile. That’s a misconception and homes built before 1976 legally can’t move. And so that kind of sparked all of our work. Some background information: in the past five to 10 years, private equity companies and big investors have been buying up mobile home parks across the country. Some of the most wealthy people in our country, like Warren Buffet, are investing in these parks. And we’re realizing more and more that it’s really because, unlike apartment units, mobile home park residents face greater barriers to moving out if the rent [for the land their home is built on] increases. To stay in their units they have to pay the price, if not, they will lose all of their own investment in homeownership.

Our coalition was able to pass the opportunity to purchase, which is similar to the right of first refusal, but not as strong. It makes it so that residents have a 90 day period to come together and put the funds necessary, and get approval from fellow residents to purchase the park. That passed in 2020 and since that law passed, 80 parks have gone up for sale. Most of them are not slated for displacement, which is great, but when private equity companies come, evictions and displacements still happen because of rent increases or landlords forcing the mobile homeowners to sign new contracts with different fees and different regulations that are really problematic. And so that was a big vision of ours and we’re seeing the gaps in Colorado of where we need more funding but also technical support to create community land trusts and cooperatives. We believe that permanent stability, permanent affordability is when a community can own and manage their own land and housing.

Q: Funding is a big piece of this and we’ve seen some federal funding come down. Jennie, I wonder if you could talk about how COVID-related federal funding has helped or is inserting itself into our housing crisis and what you see the long-term impact being?

JR: It’s been a whirlwind year of keeping up with not only federal funds but Colorado. We were lucky to have some state funds allocated as the pandemic hit. What we’ve been seeing is Colorado’s done a good job, I would say, with Cares Act funds which were some of the first federal funds. Now we have ARPA funds. We have ERA funds or ERAP. There are all kinds of new acronyms coming out of the federal government to deal with housing issues or other impacts from the pandemic.

There are a couple of tranches of those funds. There have been many news reports nationwide about how those funds aren’t getting out the door. The Cares Act rental assistance funds that came in to really help people pay for their rent as they lost jobs or had to stay home because of the pandemic, but that funding is now all gone. We have spent an incredible amount of money, and rightly so. But we now need more resources for rental assistance to deal with the fallout from the pandemic. There are so many households that are unstable. Colorado is kind of in the middle of the pack for distribution and we and a lot of partners including community organizing groups have been advocating directly to the state to increase the payments coming out of those resources because the timelines between when someone might apply for resources and get it were extremely long and in the meantime, they were at risk of being evicted if an eviction moratorium lifted, which it has.

One of the really important things to work on as more resources come in has been highlighted with the extreme need and pressures on the system, is that there are huge barriers to people accessing those resources and we need to make sure, as they’re rolling out the door, that there’s support within the community and for community organizations like 9to5 and others to reach people and make sure that there’s equitable access to those emergency resources. Because we know from the past, it could be easy to push money out the door, but it’s not easy to do it in an equitable manner.

And one of the other things that we are worried about and feel like there’s a need for is building capacity throughout the state to be able to deploy resources to housing programs and housing production. So we have nonprofit organizations and housing authorities across the state that are very dedicated and determined to meet the needs in their community but if they don’t have the staff, if they don’t have the training for their staff, if they don’t have pre-development funds, if they don’t have investment from philanthropy and other places to try new things, innovate on the ground, and be able to scale those new tools and innovations, we’re not going to meet our needs and we’re not going to be able to use all those federal funds that we have. So we feel like we have a real opportunity right now but we need to be really thoughtful and we need to be really supportive of or organizations that are really serving housing needs, especially in the metro area to make sure that we do all that we can with those new resources.

For more from this event, watch our recording.